Groovy code coverage issues

Lately, while working on a microservice in Groovy, I discovered interesting issues with measuring code coverage for Groovy projects. If you struggle with suspiciously low coverage yourself and don’t know what’s happening, read on.

After putting Cobertura test report of my rather thoroughly tested code into Sonar I saw surprising numbers: line coverage 95%, branch coverage 43%. Such low branch coverage? Something must be wrong…

Missed branch coverage

For the record, the project is in Groovy 2.3.2, without indy, on Java 8 and analyzed with Cobertura 2.0.3. Have a look at some of the examples of branches not covered as shown in Sonar. Line coverage in these files is reported as 100%.

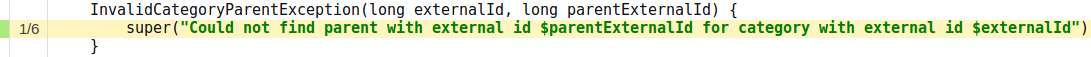

Example 1:

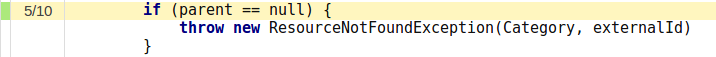

Example 2:

How come calling super in the constructor of a RuntimeException subclass counts

for 6 branches? And a simple if has as much as 10 branches? No wonder the reported

branch coverage is so low! But where do these extra branches come from? Well, what

you see in the source code is not what you get in the bytecode.

Dive into the bytecode

Let’s have a look at the first case with calling super.

59: ldc #4 // class java/lang/RuntimeException

61: invokestatic #45 // Method org/codehaus/groovy/runtime/ScriptBytecodeAdapter.selectConstructorAndTransformArguments:([Ljava/lang/Object;ILjava/lang/Class;)I

64: aload_0

65: swap

66: lookupswitch { // 5

-2020310112: 116

-1428966913: 137

-947674026: 156

-255735978: 201

39797: 232

default: 241

}

Calling super compiles into calling ScriptBytecodeAdapter.selectConstructorAndTransformArguments

from Groovy runtime package which selects the matching constructor among 5 constructors of

RuntimeException class. Together with the default case that makes for 6 branches in the

bytecode in total, out of which only one is covered by the tests.

Now, the bytecode for the second example is quite lengthy so I decided not to include it

here. In short, that simple if statement with a throw compiles into around 80 bytecode

instructions among which you can find 5 branch instructions: ifeq and ifne. You would

expect only a single branch instruction, but Groovy complicates the compiled code by

including some performance optimizations. Unfortunately, some of the resulting optimization

branches were not reached from the unit tests.

Partial solution – disable groovy optimizations

While we cannot do anything with the first case, we can control optimizations performed by Groovy. It is possible to compile the sources with all optimizations disabled. This way the bytecode for the second case is reduced to 40 instructions with only a single branch instruction. As a result only 2 branches are reported by Cobertura, all of them covered.

You probably don’t want to disable the optimizations in your production build, just in your separate Sonar build. If you use Gradle, you can achieve this for example this way:

gradle.taskGraph.whenReady { graph ->

if (graph.hasTask(':cobertura')) {

compileGroovy.groovyOptions.optimizationOptions.all = false

}

}

After disabling the optimizations the number of false negatives in the Cobertura report decreases. In my project this led to an increase of over 5% in the reported branch coverage. Not much, but closer to truth.

Enabling invoke dynamic support increased the branch coverage by 3%, whether with or without optimizations. I haven’t analyzed this deeply though.

Trying Jacoco

Jacoco is the second of the two main opensource coverage measuring tools. I applied

its latest version, 0.7.1.201405082137, on my project and the reported coverages were

even more off: line coverage 33%, branch coverage 9%. Disabling the optimizations

increased the line coverage to 48% and branch coverage to 12% however. This difference

compared to Cobertura results comes from Jacoco detecting Groovy generated code

(e.g. by @Immutable transformation) and reporting it as not covered – which Cobertura didn’t do.

Conclusions

There’s not much you can do about incorrect code coverage reported by these opensource tools. They are written with Java in mind and support for other languages is still somewhere in their roadmap. Actually, I haven’t tried another popular tool – Clover. It’s not free, but perhaps it supports Groovy better.

On the bright side, I read Peter Niederwieser – an active member of the Groovy community – saying that the situation might improve with Groovy 3.0, which will be designed around Java invokedynamic, meaning that less “magic” byte code will have to be generated. And that gives us hope for the future.